2018’s Beastie Boys Book tried its best. The chatty autobiography/fan document is cute for about 30 of its 500 pages. Their myth has taken on too much baggage - 80’s/90’s nostalgia, industry perks, celebrity friends. And it’s incomplete, due to the passing of Adam Yauch in 2012. The two surviving members lost their brother, and their moral center. There can’t really be a Beastie Boys anything again.

So it’s worthwhile to offer a fresh take, and not fresh as in “Step into the party with the Fila fresh gear/ People looking at me like I was David Koresh here.” But fresh as in reevaluation. The inclination is to rescue them from the detritus of nostalgic pop culture. They won their fanbase organically, the hard way. Parking lot skaters and basement burnouts, riot grrrls and hip hop heads - these groups were more jaded than corporate executives. The music did it, mostly, but so did the ethics. They cultivated a culture of elite cool that was accessible to anyone.

The kids who made Licensed To Ill acted as if their whiteness wasn’t a thing and good taste was for the birds. In hindsight - the album seems stupid and obvious. Why not marry Led Zeppelin’s mightiest drum beat with Black Sabbath’s grooviest riff? (And why even bother, if it was going to inspire Kid Rock’s career?) The album worked because their spin on Run-DMCisms (“White Castle fries only come in one size”) was unique and fun and genuine. That’s what rap was in 1986. It existed as a new wave in music to be explored and experimented with.

Their disavowals of that early era - “we were mocking frat boy culture” - seem disingenuous and a little beside the point. Let’s not retroactively assign forethought to good fun, bratty and boorish as it was. Their rise went from opening for Madonna to co-headlining with Run-DMC, settling in the public consciousness as a Weird Al-adjacent novelty act. Meanwhile rap music was evolving, finding its voice with Rakim and Boogie Down Productions and Public Enemy. After acrimoniously leaving Def Jam Records, they were accused by their whiteboy replacements 3rd Bass of mocking the culture. That charge would soon become moot.

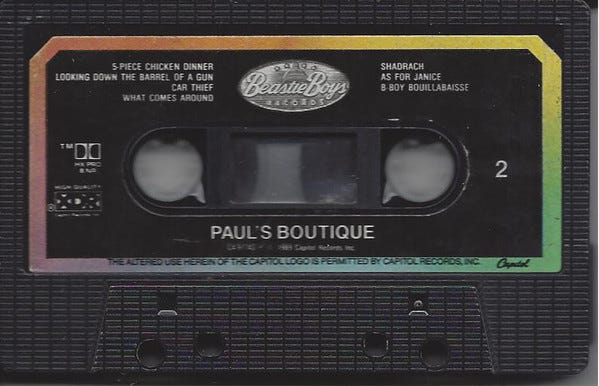

1989’s Paul’s Boutique was an evolutionary leap. Creative sampling, layering grooves and loops into dense new songs, was at its peak. So the Dust Brothers gifted them a beat template so ingeniously dope that it had to be met as such, lyrically. A side note - Rick Rubin, the producer of Licensed To Ill and music industry “guru,” was by then so outpaced and outclassed by Public Enemy’s Bomb Squad and De La Soul’s Prince Paul that he disappeared from hip hop altogether. Good riddance, said the Beastie Boys, who kept whatever beef they had with him quiet. Their beef with Russell Simmons, head honcho of Def Jam, was more public. “Car Thief” is emblematic of Paul’s Boutique - a funky loop buried by noises and sampled fragments builds with subtle dynamics, while the Beasties rap about cocaine and a stealing motif that serves as a diss to Simmons.

The album gives us a picture of their world and their distinct personalities within it - Mike D as the pop culture devotee, Ad-Rock as the womanizer of Hollywood starlets, and MCA as the outlaw renegade and occasional voice of reason. It also speaks to postmodernism ideals, with the playful blend of pop culture and philosophy, and an emphasis on how it was made. A postmodern work should be dense and dizzying but also transparent, so that its process becomes its purpose. What the hell drugs were they on? They tell us. Even the jokes that fall flat still work: “Droppin’ science like Galileo dropped an orange.”

The Beastie Boys as rappers could not compete in the ‘90s. God bless them for recognizing that, and not attempting long poetic verses like Nas or Andre 3000. Moreover - Paul’s Boutique kind of bombed initially. They didn’t tour the album, and didn’t bother trying to repeat it. So invention became the key to their next phase.

1992’s Check Your Head presented a new fully formed sound. Or sounds, as they performed their own funky instrumentals and psychedelic chants along with the distorted vocal rap songs. The secret to the album is its spin on boom bap, then in vogue with heavy drums and scratchy bass-enhanced samples. On “Pass The Mic” and “So What’cha Want” they replicated boom bap on their own instruments, lending the sound a distinctively harder edge. Which drew in punk kids, and skaters, and the alternative rock crowd.

1994’s Ill Communication has aged even better, as it subtly inverts the previous album’s formula. Are the rap songs now just filler for the prog, funk, and punk excursions? The album asks, and answers, a larger question - why are your tastes as a listener more eclectic than the bands you follow? Why do artists who try to mix rap and rock seem so mediocre if not horrid at both? Perhaps it’s a moot point in 2024, when the genres have merged or morphed into new forms. Ill Communication saw the future, with humor and an intuitively abstract design.

1998’s Hello Nasty is the victory lap, a little less urgent and more self-indulgent. Their eclecticism is almost rote, so we’re not surprised by folk pop and baroque ‘60s psych songs. Nor the absurd weirdness, nor the inclusion of an obvious hit single (“Intergalactic”). The whole formula worked because they always had the sense to keep their songs hooky and memorable. Rare is the Beastie Boys track that is flat out dull. If Hello Nasty is a little too comfortable with itself, that’s understandable. They ran the race their way, taking every wild path imaginable, and they won.

The Tibetan Freedom concerts were the high mark of their cultural leadership. The cause was noble, and fit their vibe of likeminded inclusivity. The acts on those bills represented the best side of ‘90s culture, a sort of anti-Woodstock ‘99. They also stretched the Beastie dynamic as far as it would go. Because really, what was next? Mike D runs for Senate? That would be beneath him.

This reckoning came to the fore on 2004’s To The Five Boroughs. Their worst album by a mile, it was doomed from the start. They decided - or Yauch did, according to their book - that it would be all rap songs. Never the best rappers even at their peak, their skills had regressed to sub-Run-DMC levels. The “we’re MCs and we’re here to say” shtick was beyond played out, all the more when it was used for serious messaging. And worse, they didn’t seem to have much to say. They were just rhyming simple words, nothing more.

They followed it with an instrumental album, and the surprisingly solid Hot Sauce Committee Part Two in 2011. Still that project was overshadowed by the sickness and passing of Adam Yauch. There could be no band without any one of them. Mike D was the scenester who kept them up to date, and the deadpan funniest, Ad-Rock was sonically the best rapper, the most sampled voice by other acts, but Yauch was a special creative force, their best musician on the bass who drove their ‘90s renaissance, with the widest and most humane ambitions.

Regardless, the Beastie Boys as a thing ended in 1999. They said as much, with that year’s release of a greatest hits/outtake collection. Discerning fans saw that as a sign more than a potential purchase. We already had those songs, the B-sides too. But it was a good message, that rectified the bad one left by Kurt Cobain. It actually is better to fade away than burn out.